Introduction to birth control

Introduction to birth control

If a woman is sexually active and she is fertile and physically able to become pregnant, she needs to ask herself, "Do I want to become pregnant now?" If her answer is "No," she must use some method of birth control (contraception).

Terminology used to describe birth control methods include contraception, pregnancy prevention, fertility control, and family planning. But no matter what the terminology, sexually active people can choose from an abundance of methods to reduce the possibility of their becoming pregnant. Nevertheless, no method of birth control available today offers perfect protection against sexually transmitted infections (sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs), except abstinence.

In simple terms, all methods of birth control are based on either preventing a man's sperm from reaching and entering a woman's egg (fertilization) or preventing the fertilized egg from implanting in the woman's uterus (her womb) and starting to grow. New methods of birth control are being developed and tested all the time. And what is appropriate for a couple at one point may change with time and circumstances.

Unfortunately, no birth control method, except abstinence, is considered to be 100% effective.

Permanent methods of contraception (surgical sterilization)

Sterilization is considered a permanent method of contraception. In certain cases, sterilization can be reversed, but the success of this procedure is not guaranteed. For this reason, sterilization is meant for men and women who do not in

Sterilization is considered a permanent method of contraception. In certain cases, sterilization can be reversed, but the success of this procedure is not guaranteed. For this reason, sterilization is meant for men and women who do not inVasectomy

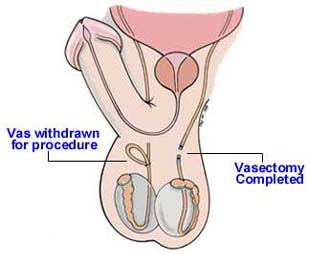

A vasectomy is a form of sterilization of a man. A vasectomy ensures that no sperm will exit from his penis when he ejaculates during sexual intercourse.

A vasectomy is usually performed by either a urologist or a general surgeon. Under local anesthesia, the vas deferens (tubes that carry sperm from the testicles into the urethra, also known as spermatic ducts) from each testicle is severed. The open ends are then closed off. A vasectomy can be performed in the clinic and involves making two small openings in the scrotum. After a vasectomy, the man may feel tenderness or bruising around the incision site.

A vasectomy does not interfere with the ability of a man to have an erection or the quantity of his ejaculation fluid. After a man has a vasectomy, another second form of birth control should be used until his ejaculate fluid is found to be free from sperm. This usually takes 10 to 20 ejaculations.

A vasectomy does not interfere with the ability of a man to have an erection or the quantity of his ejaculation fluid. After a man has a vasectomy, another second form of birth control should be used until his ejaculate fluid is found to be free from sperm. This usually takes 10 to 20 ejaculations.

Vasectomy reversals are possible, but they tend to be expensive and are not guaranteed to be effective. A vasectomy should be considered a permanent form of birth control.

A vasectomy does not protect a man or his partner from sexually transmitted infections.

Tubal ligation

Tubal ligation

Tubal ligation is also known as "having one's tubes tied," or having a "tubal." Tubal ligation is for women, and like a vasectomy, should be considered a permanent form of birth control.

A tubal ligation is performed under general, regional, or local anesthesia and can be performed as an outpatient procedure. The surgeon or ob/gyn uses one of several procedures in order to access a woman's Fallopian tubes (which run from the top part of her uterus to each ovary). A laparoscopy is a procedure in which a small incision is made just below the navel. A viewing tube (scope) can then be inserted through this incision to view and reach the Fallopian tubes. A minilaparotomy is a small incision in the lower abdomen that is sometimes used for tubal ligation most commonly in the postpartum period (after childbirth).

Once the physician has access to a woman's Fallopian tubes, they are closed off by using a clip, cutting and tying, or cauterizing (burning) the tubes. The procedure takes anywhere from 10 to 45 minutes.

Side effects of a tubal ligation may include infection, bleeding (hemorrhage), and those associated with being under general anesthesia.

A tubal ligation blocks a woman's Fallopian tubes. As a result of the procedure, about 1 inch of each tube is blocked off. An egg can no longer travel down the tube to the uterus, and sperm cannot make contact with the egg. Tubal ligation should have no effect on a woman's menstrual cycle or hormone production.

A woman's tubal ligation can be surgically reversed, usually with more success than in men who have had a vasectomy. About 1% to 2% of women in the US seek a reversal of tubal ligation.

A tubal ligation does not protect a woman or her partner from sexually transmitted infections (sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs). It is also not an absolute method of birth control because a small percentage of women become pregnant after a tubal ligation. Pregnancy after tubal ligation is uncommon (occurring in less than 2% of women), and the risk of pregnancy appears to be related to age (younger women have more post-tubal ligation pregnancies) as well as the type of procedure used for the sterilization.

A tubal ligation does not protect a woman or her partner from sexually transmitted infections (sexually transmitted diseases, or STDs). It is also not an absolute method of birth control because a small percentage of women become pregnant after a tubal ligation. Pregnancy after tubal ligation is uncommon (occurring in less than 2% of women), and the risk of pregnancy appears to be related to age (younger women have more post-tubal ligation pregnancies) as well as the type of procedure used for the sterilization.

Post-tubal ligation syndrome

A condition referred to as "post-tubal ligation syndrome" (or post-tubal sterilization syndrome) has been the subject of debate in recent years. Proponents argue that women who have had tubal ligations are prone to menstrual irregularities and symptoms such as hot flashes and mood changes as a result of damage to the blood supply to the ovaries as a result of the procedure. This syndrome has also been described as consisting of symptoms such as changes in sexual behavior and emotional health, exacerbation of premenstrual symptoms, and menstrual symptomsnecessitating hysterectomy or tubal reanastomosis. A study of over 9500 women reported in 2000 in the New England Journal of Medicine, failed to confirm any association between tubal sterilization and menstrual problems, but some investigators suggest that a minority of women do report menstrual problems or other symptoms following the procedure.

Hysteroscopic sterilization

Hysteroscopic sterilization is a nonsurgical form of permanent birth control in which a physician inserts a 4-centimeter (1.6 inch) long metal coil into each one of a woman's two Fallopian tubes via a scope passed through the cervix into the uterus (hysteroscope), and from there into the openings of the Fallopian tubes. Over the next few months, tissue grows over the coil to form a plug that prevents fertilized eggs from traveling from the ovaries to the uterus.

The procedure takes about 30 minutes, can be done in a doctor's office, and usually requires only a local anesthetic. During a 3-month period after the coils are inserted, women must use other forms of birth control until their physician verifies by an imaging test known as a hysterosalpingogram(HSG) that the Fallopian tubes are completely blocked.

Like tubal ligation, this form of sterilization is permanent (not reversible) and is designed as an alternative to surgical sterilization which requires general anesthesia and an incision. About 6% of women who have the procedure develop side effects, mainly due to improper placement of the coils.

This form of sterilization, like other methods of surgical sterilization, does not protect a woman or her partner from sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is the surgical removal of a woman's uterus and, depending on her overall health status and the reason for the operation, perhaps her ovaries as well. No woman who has had a hysterectomy can become pregnant; it is an irreversible method of birth control and absolute sterilization. A laparoscopic hysterectomy (removal of the uterus through tiny incisions in the abdomen through which instruments are placed) is possible when there are no complications and no suspicion of cancer. A partial hysterectomy, which spares the cervix and removes the upper part of the uterus, is also a common surgical technique.

If a woman has other chronic medical problems that may be helped by a hysterectomy (such as abnormally excessive menstrual bleeding, uterine fibroids, uterine growths), than this may be an appropriate procedure for her to consider. Otherwise, contraception should be considered a secondary benefit and not a sole reason to have the procedure.

REFERENCES:

Peterson HB, Jeng G, Folger SG, Hillis SA, Marchbanks PA, Wilcox LS; U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. The risk of menstrual abnormalities after tubal sterilization. U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Dec 7;343(23):1681-7.

Previous contributing authors: Barbara K. Hecht, Ph.D. and Carolyn Janet Crandall, MD, FACP

Peterson HB, Jeng G, Folger SG, Hillis SA, Marchbanks PA, Wilcox LS; U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. The risk of menstrual abnormalities after tubal sterilization. U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Dec 7;343(23):1681-7.

Previous contributing authors: Barbara K. Hecht, Ph.D. and Carolyn Janet Crandall, MD, FACP