Hundreds of women who received faulty breast implants gathered

Wednesday in a makeshift courthouse in the south of France for the fraud

trial of five executives accused of using cheap industrial silicone to

fill tens of thousands of implants that were sold around the world.

Hundreds of women who received faulty breast implants gathered

Wednesday in a makeshift courthouse in the south of France for the fraud

trial of five executives accused of using cheap industrial silicone to

fill tens of thousands of implants that were sold around the world.Jean-Claude Mas, who founded and ran implant-maker Poly Implant Prothese, is among those on trial in the southern city of Marseille. The now-defunct company had claimed its factory in France exported to more than 60 countries and was one of the world's leading implant makers.

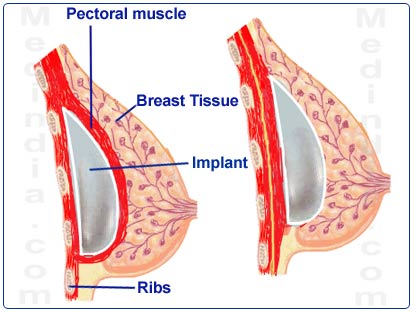

The implants, which officials say are prone to rupture and leaking, were not sold in the United States, but more than 125,000 women worldwide received them until sales ended in March 2010. Of those, more than 5,000 are joining the trial as victims, saying the executives misled them into believing the implants were safe.

Nathalie De Michel, who received the implants, said Wednesday she wanted Mas to acknowledge responsibility.

"We have the impression that he doesn't care. I want him at least to recognize that he made mistakes. When you fight against cancer, you fight to survive, and if after they put some garbage in your body, what's the point of fighting for life?"

Mas declined comment as he entered the convention center — which was turned into a courthouse to host all those participating in the trial — in order to face the women for the first time.

The vast majority of the implants were for cosmetic reasons. The rest were for breast reconstruction, often following cancer surgery. Within France, about a quarter of the implants malfunctioned, most by rupturing and leaking silicone, according to a government tally released earlier this month.

Doctors and scientists who have followed the case say medical complications stemming from the ruptures and leaks appear to be limited even when the implants rupture: rashes and localized pain were the most common complaints. But lawyers for the women — more than 300 from around the world who joined the month-long trial — say the full effects will not be known for years to come.

Nataly Lozano, a Colombian lawyer who said she represents 1,500 women she says have had problems with the PIP implants, said she came to Marseille to seek justice for clients she says lack the resources to pay for follow-up care.

"I could name very difficult cases of women who don't even have means to undergo exams and know what state their implants are in," she said. "They know that they are dangerous implants and nevertheless they don't even have a way to know if their implants are broken inside their body, if eventually this substance will leak into their body."

The implants in question were not sold in the U.S., where concerns about silicone gel implants overall led to a 14-year ban on their use. Silicone implants were brought back to the market in 2006 after research ruled out cancer, lupus and some other concerns, but the FDA still cautions that implants of any kind can rupture or cause other problems.

The French government recommended that women have their PIP implants removed as a precaution, and about a third of Frenchwomen who had the implants did so, according to the April 2013 government report.

In Britain, the government left the choice up to women and their doctors, but recommended that the implants be removed if there was a sign of rupture.

The company ultimately went out of business, and regulators across Europe began demanding calls for tighter oversight of medical devices. Mas has said he is ruined financially.

According to various government estimates, over 42,000 women in Britain received the implants, more than 30,000 in France, 25,000 in Brazil and 15,000 in Colombia. Venezuela, where PIP implants were hugely popular, offered free removals for the estimated 16,000 women with the implants, as did France.

Mas, his deputy Claude Couty, the quality director Hannelore Font, technical director Loic Gossart, and products chief Thierry Brinon face the possibility of five years in prison if convicted.