Pregnant women exposed to phthalates, a group of hormone-mimicking

chemicals found in personal care products and processed foods, may have

an increased risk of preterm delivery, a new study suggests.

The study included 130 women in the Boston area who had given birth early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy, and 352 women who delivered at full term between 2006 and 2008. The researchers measured the levels of common phthalates such as DEHPin the women's urine up to three times during their pregnancies.

such as DEHPin the women's urine up to three times during their pregnancies.

They found that women who had the highest levels of phthalate metabolites in their urine had a risk of preterm birth that was two to five times higher when compared with women who had the lowest levels.

that was two to five times higher when compared with women who had the lowest levels.

What's more, when the researchers looked only at the 57 women who had "spontaneous preterm delivery," meaning they didn't have a medical condition that could explain their early delivery, they found the link between exposure to phthalates and risk of preterm delivery was stronger, according to the study published today (Nov. 18) in JAMA Pediatrics.

"These data provide strong support for taking action in the prevention or reduction of phthalate exposure during pregnancy," the researchers wrote in their findings.

Phthalates are chemicals widely used in making flexible and durable

plastics, and many other products such as adhesives, detergents, soaps,

shampoos, hair sprays, perfumes and deodorants. People are exposed to

these potentially hormone-disrupting chemicals through contact with

phthalate-containing products, and eating certain processed and canned

foods. [12 Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals & Their Health Effects

Phthalates are chemicals widely used in making flexible and durable

plastics, and many other products such as adhesives, detergents, soaps,

shampoos, hair sprays, perfumes and deodorants. People are exposed to

these potentially hormone-disrupting chemicals through contact with

phthalate-containing products, and eating certain processed and canned

foods. [12 Hormone-Disrupting Chemicals & Their Health Effects ]

]

"For women who are interested in reducing their exposure, reducing use of personal care products, buying phthalate-free [products] when possible, and eating fresher foods may help, although research on that is limited," said study researcher John Meeker, an associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences at University of Michigan School of Public Health.

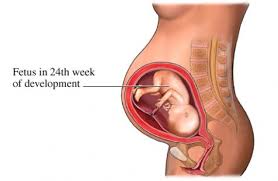

Preterm birth, defined as the birth of an infant before 37 weeks of pregnancy, is a leading cause of death or long-term neurological disabilities in children. The rate of preterm birth in the United States has increased by more than a third between 1981 and its peak at 12.8 percent in 2006. The rates slightly decreased in the subsequent years ,

to about 11.5 percent in 2012, which means one out of every eight

children is now born prematurely, according to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC).

,

to about 11.5 percent in 2012, which means one out of every eight

children is now born prematurely, according to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC).

A recent review of studies looking for what might underlie the

increase in preterm birth rates identified risk factors such as

increasing maternal age and use of assisted reproduction. However,

nearly half of the increase remains unaccounted for, said Shanna Swan, a

professor of preventive medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount

Sinai, New York.

A recent review of studies looking for what might underlie the

increase in preterm birth rates identified risk factors such as

increasing maternal age and use of assisted reproduction. However,

nearly half of the increase remains unaccounted for, said Shanna Swan, a

professor of preventive medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount

Sinai, New York.

The new study provides "strong evidence that environmental chemicals, and phthalates in particular, likely contribute significantly to that unknown and other category," Swan wrote in an editorial published along with the new study.

The study showed an association, not a cause-and-effect relationship, between phthalates and preterm birth. However, there are reasons to think phthalates could cause preterm births; for example, phthalates may cause inflammation in the uterine lining, the researchers said.

Lab studies have shown that phthalates can cause inflammation, but this needs to be studied in humans. Other ideas about possible mechanisms by which phthalates affect pregnancy involve women's immune response , oxidative stress, and hormone disruption.

, oxidative stress, and hormone disruption.

"There's a list of things phthalates have been shown to do in experimental studies. Much work is left to be done in human observational studies," Meeker told LiveScience.

Other factors that contribute to higher risks of preterm delivery include smoking, drinking, infection, stress and high blood pressure during pregnancy. A study published in January 2013 in the journal Lancet predicted that current interventions to address known risk factors would decrease preterm birth rates by only 5 percent by 2015.

Exposure to phthalates may be one risk factor that could be prevented by behavioral modification or through policies aiming at reducing the use of phthalates, the researchers said.

The study included 130 women in the Boston area who had given birth early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy, and 352 women who delivered at full term between 2006 and 2008. The researchers measured the levels of common phthalates

They found that women who had the highest levels of phthalate metabolites in their urine had a risk of preterm birth

What's more, when the researchers looked only at the 57 women who had "spontaneous preterm delivery," meaning they didn't have a medical condition that could explain their early delivery, they found the link between exposure to phthalates and risk of preterm delivery was stronger, according to the study published today (Nov. 18) in JAMA Pediatrics.

"These data provide strong support for taking action in the prevention or reduction of phthalate exposure during pregnancy," the researchers wrote in their findings.

"For women who are interested in reducing their exposure, reducing use of personal care products, buying phthalate-free [products] when possible, and eating fresher foods may help, although research on that is limited," said study researcher John Meeker, an associate professor of Environmental Health Sciences at University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Preterm birth, defined as the birth of an infant before 37 weeks of pregnancy, is a leading cause of death or long-term neurological disabilities in children. The rate of preterm birth in the United States has increased by more than a third between 1981 and its peak at 12.8 percent in 2006. The rates slightly decreased in the subsequent years

The new study provides "strong evidence that environmental chemicals, and phthalates in particular, likely contribute significantly to that unknown and other category," Swan wrote in an editorial published along with the new study.

The study showed an association, not a cause-and-effect relationship, between phthalates and preterm birth. However, there are reasons to think phthalates could cause preterm births; for example, phthalates may cause inflammation in the uterine lining, the researchers said.

Lab studies have shown that phthalates can cause inflammation, but this needs to be studied in humans. Other ideas about possible mechanisms by which phthalates affect pregnancy involve women's immune response

"There's a list of things phthalates have been shown to do in experimental studies. Much work is left to be done in human observational studies," Meeker told LiveScience.

Other factors that contribute to higher risks of preterm delivery include smoking, drinking, infection, stress and high blood pressure during pregnancy. A study published in January 2013 in the journal Lancet predicted that current interventions to address known risk factors would decrease preterm birth rates by only 5 percent by 2015.

Exposure to phthalates may be one risk factor that could be prevented by behavioral modification or through policies aiming at reducing the use of phthalates, the researchers said.